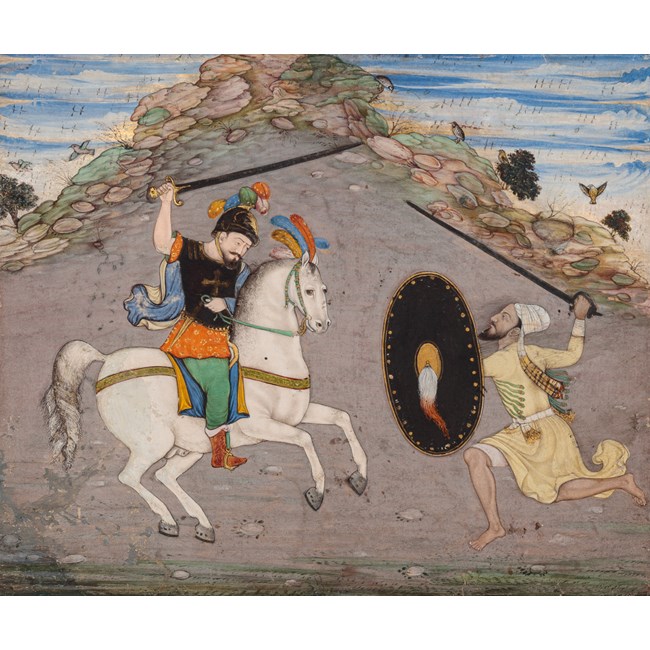

Sword Fight Between a Christian Horseman and an Indian Soldier

Sword Fight Between a Christian Horseman and an Indian Soldier

Sword Fight Between a Christian Horseman and an Indian Soldier

Mughal India c. 1600

Opaque Watercolour - Gold on Paper

Provenance:Collection of Lavinia, Marchioness of Cholmondeley (1921-2015), thence by descent

12.4cm high, 14.8cm wide

Stock No.: A5428

Sword Fight Between a Christian Horseman and an Indian Soldier

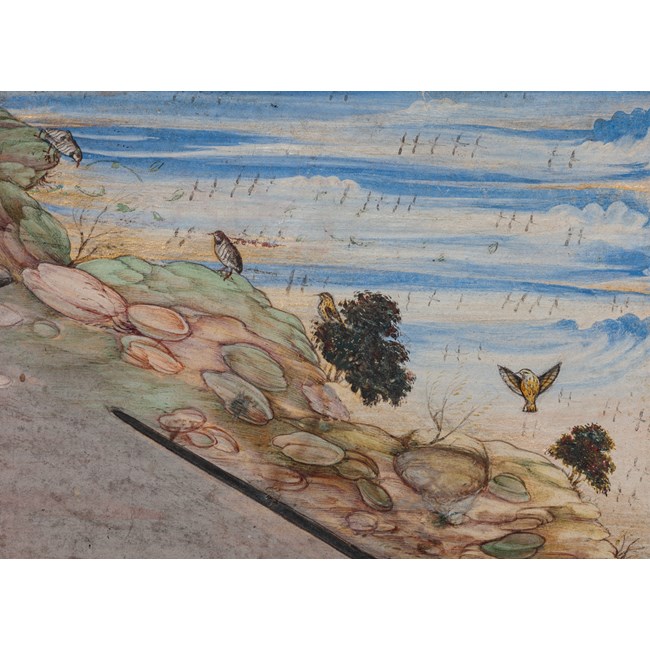

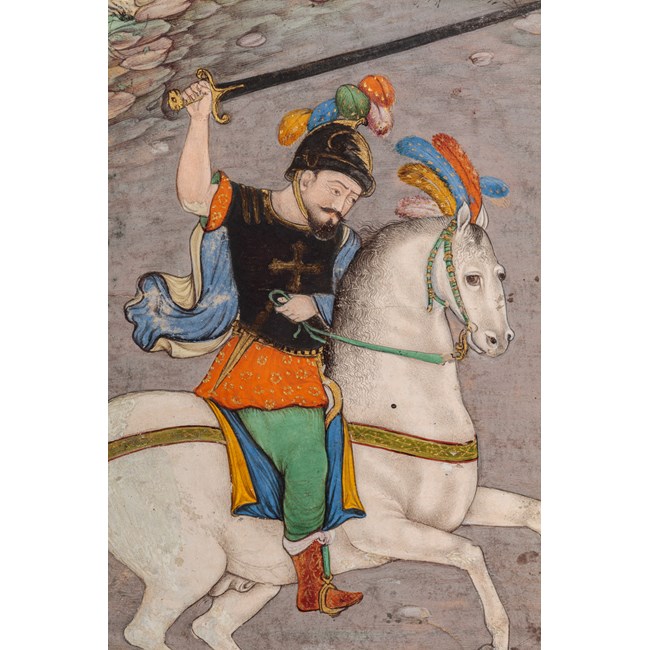

The scene depicted in this rare, unusual Mughal painting evokes contemporary depictions of Saint James the Moor-slayer. It may illustrate the story of the miraculous apparition of the Apostle Saint James the Great (d. 44 CE), also known in Spanish as Santiago Matamoros (Moor-slayer). According to Spanish legend, the saint appeared in 844 at the Battle of Clavijo (La Rioja) leading the Christian forces to victory over the Muslim invaders. In this painting the saint is portrayed riding triumphantly on a rearing white horse in combat with a Muslim foot soldier. Saint James’ attire corresponds with items of clothing used by the Portuguese in India in the late sixteenth century, namely a long-skirted jerkin (roupeta) with a cuirass featuring a fleur-de-lysed cross on the breastplate, loose-fitting hoses, boots and a burgonet decorated with plumes. Conversely, the barefoot ‘Moor’ is depicted as a contemporary local Indian soldier wearing a long double-breasted coat (jāma) with its many tying laces, over short tight-fitting trousers (shalwār), a decorated waist sash (paṭkā), and a small turban (kulahdār).[1] While Saint James brandishes a European long sword with a lion-shaped pommel, the Indian soldier wields a khāṇḍa, a typical Hindu fighting sword fitted with a double-edged straight blade and basket hilt.[2] The ‘Moor’ also sports a round convex black shield, a Hindu dhāl probably of leather decorated with dome-shaped gilt nails on the rim and yak tail hair hanging from the centre.[3]

Albeit a specific Iberian iconography, the theme of Saint James the Moor-slayer circulated in print form since the late fifteenth century, while the Battle of Clavijo was depicted by Peeter Baltens and engraved by Antonio Tempesta around 1600.[4] After his victory in Tunis in 1535, emperor Charles V (r. 1519-1556) got himself portrayed as Saint James the Moor-Slayer by an unidentified Antwerp painter now in the Worcester Art Museum (inv. 1934.64).[5] This was an allegorical painting charged with powerful political connotations, somewhat similar to those expressed in this Mughal painting. There are, however, some typical iconographic details that are absent from the present painting. Usually, the saint is depicted with the red Cross of Saint James, the symbol of the Order of Santiago, on his chest. In contrast, the golden fleur-de-lysed cross depicted is that of the Order of Calatrava (Spanish, red) or the Order of Avis (Portuguese, green). The saint is also generally depicted trampling over his defeated, dismembered Muslim enemies, and not engaging is this somewhat more balanced manner. The intention of the painter may have been merely to illustrate the archetypical conflict between Christians and Muslims, and not an actual battle between Portuguese and local Indian soldiers, nor the story of Santiago Matamoros. Whatever the case, this depiction seems to be a peculiar choice of subject matter considering that it was most probably made at the painting workshop of a Muslim ruler, likely at the Mughal imperial workshops during the later years of emperor Akbar’s (r. 1556-1605) or the early years of Jahangir’s (r. 1605-1627) rule.

The first meaningful contacts between Europeans and Mughals began in 1573 after Akbar’s conquest of Gujarat.[6] The emperor encountered the first Portuguese in Surat, and as result, decided to send a mission to Goa in 1575 led by Haji Habibullah.[7] For two years the many artists and craftsmen that accompanied him learned new crafts and ultimately introduced them to the imperial workshops. This mission was soon followed by that of Tahir Muhammad in 1580-1581 with the same orders to bring back specific articles in addition to expert artisans and musicians, satisfying the emperor’s desire for ‘objects of wonder and rarity’ and qualified craftsmen to produce them. This, in turn, fuelled by the emperor’s religious curiosity, led to the first of several Jesuit missions from Goa to the Mughal court starting in 1582.[8] Bringing prints and paintings that were shown to royal artists who copy them at the emperor’s request, the Jesuit priests with their novel imagery helped to infuse new artistic ideas with lasting consequences for the development of a Mughal artistic idiom. While some of the works produced at this time copy faithfully the European models provided by prints and paintings, the present composition seems to have been only loosely inspired, mostly in the depiction of the European soldier and his horse.

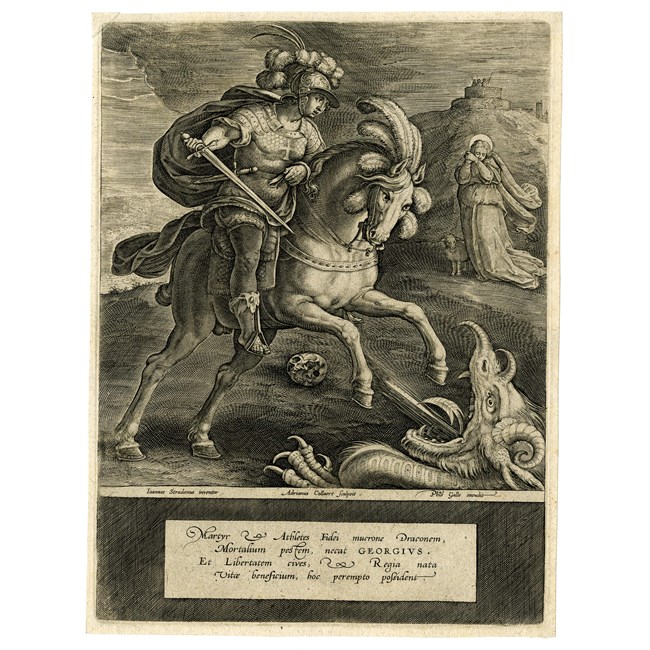

Given the Jesuit connection, it is not surprising that the closest parallel that could be found, seemingly used as a model by the Mughal artist (likely of local Indian origin) is this religious print. Made by Adriaen Collaert (c. 1560-1618) after a design by Jan van der Straet, better known as Johannes Stradanus (1523-1605), and published c. 1580-1600 by Philips Galle, it depicts Saint George Killing the Dragon. Although the more vigorous pose of the horse is not followed by the Indian painter, nor the position of the right hand holding the long sword, both the overall attire of the painted European horseman, the cross on his chest, the position of the left hand holding firmly the horse reins against his chest, the hanging dagger, and the plumes adorning his helmet and the horse’s head, all match closely those on the print. In addition, Stradanus’ famous series on the horse breeds belonging to John of Austria, the illegitimate son of Emperor Charles V, titled Equile Ioannis Austriaci) published around 1578 may have provided the model (possibly Gallicus) onto which the Mughal artist based the design of the horse in this painting. And although the Indian soldier was not modelled after any print, as it is unlikely that any depiction of this specific type of clothing would be known by European artists, it should be underscored that the realistic treatment and careful shading of his billowing jāma are similar to that of the European horseman’s clothes.[9] The naturalistic rendering, style, and vibrant colouring of the present painting are reminiscent of well-known compositions more closely based on European printed models. These include for instance Kesu Das’ Joseph Telling his Dream to his Father, painted around 1590 and based on a 1544 engraving by Georg Pencz; and a painting depicting The Martyrdom of Saint Cecilia by the artist Nini based on an engraving by Hieronymus Wierix from c. 1599-1605.[10]

Probably once set on an album page, this painting, with its careful execution, detailed depiction of items of clothing, arms and armour, and unexpected iconography, stands as a distinctive and historically significant testimony of the religious and artistic entanglements between Europe and Mughal India in the so-called Age of Discovery.

Literature:

Gauvin Alexander Bailey, The Jesuits and the Grand Mogul. Renaissance Art at the Imperial Court of India, 1580-1630, Washington, Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “Between Religions: Christianity in a Muslim Empire”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal (cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 148-161.

Milo C. Beach, “Visions of the West in Mughal Art”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal (cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 169-189.

Hugo Miguel Crespo, “Indian diamonds and the Portuguese during the rise of the Mughal empire”, in Usha R. Balakrishnan (ed.), Diamonds Across Time. Facets of Mankind, London, The World Diamond Museum, 2020, pp. 175-217.

Asok Kumar Das, “Prince Salim and Christian Art”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal (cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 162-169.

Robert Elgood, Hindu Arms and Ritual. Arms and Armour from India, 1400-1865, Delft, Eburon Academic Publishers, 2004.

Robert Elgood, “Mughal Arms and the Indian Court Tradition”, Jewellery Studies, 10 (2004), pp. 76-98.

Jorge Flores, The Mughal Padshah. A Jesuit Treatise on emperor Jahangir’s Court and Household, Leiden - Boston, Brill, 2016.

Jan van Herwaarden, “The Emperor Charles V as Santiago Matamoros”, Peregrinations. Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3.3 (2012), pp. 83-106.

Mika Natif, Mughal Occidentalism. Artistic Encounters between Europe and Asia at the Courts of India, 1580-1630, Leiden, Brill, 2018.

Som Prakash Verma, Art and Material Culture in the Paintings of Akbar’s Court, New Delhi, Vikas Publishing House, 1978.

Footnotes:

[1] On these items of clothing, see Som Prakash Verma, Art and Material Culture in the Paintings of Akbar’s Court, New Delhi, Vikas Publishing House, 1978, pp. 47-53.

[2] On the khāṇḍa sword, see Robert Elgood, Hindu Arms and Ritual. Arms and Armour from India, 1400-1865, Delft, Eburon Academic Publishers, 2004, pp. 79-100. On the use of mostly Indian-origin arms at the Mughal court, see Robert Elgood, “Mughal Arms and the Indian Court Tradition”, Jewellery Studies, 10 (2004), pp. 76-98.

[3] Round shields embellished with the fluff of yaks’ tails were used by the Mughal guards. See Prakash Verma, Art and Material Culture in the Paintings of Akbar’s Court, New Delhi, Vikas Publishing House, 1978, pp. 85-86.

[4] A copy of this engraving belongs to the collection of the British Museum, London, inv. X,3.83.

[5] See Jan van Herwaarden, “The Emperor Charles V as Santiago Matamoros”, Peregrinations. Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3.3 (2012), pp. 83-106.

[6] See Jorge Flores, The Mughal Padshah. A Jesuit Treatise on emperor Jahangir’s Court and Household, Leiden - Boston, Brill, 2016, maxime, pp. 10-21; and Jorge Flores, Unwanted Neighbours. The Mughals, the Portuguese, and Their Frontier Zones, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2018.

[7] See Mika Natif, Mughal Occidentalism. Artistic Encounters between Europe and Asia at the Courts of India, 1580-1630, Leiden, Brill, 2018, pp. 37-38; and Hugo Miguel Crespo, “Indian diamonds and the Portuguese during the rise of the Mughal empire”, in Usha R. Balakrishnan (ed.), Diamonds Across Time. Facets of Mankind, London, The World Diamond Museum, 2020, pp. 201-203.

[8] For the artistic aspects of this interaction, see Gauvin Alexander Bailey, The Jesuits and the Grand Mogul. Renaissance Art at the Imperial Court of India, 1580-1630, Washington, Smithsonian Institution, 1998; Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “Between Religions: Christianity in a Muslim Empire”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal (cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 148-161; Asok Kumar Das, “Prince Salim and Christian Art”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal(cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 162-169; and Milo C. Beach, “Visions of the West in Mughal Art”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal (cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 169-189.

[9] On such subtle differences, see Kavita Singh, Real Birds in Imagined Gardens. Mughal Painting between Persia and Europe, Los Angeles, The Getty Research Institute, 2017.

[10] The first in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (inv. IN.41.2), and the second in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (inv. IM.139A-1921). Nonetheless, both compositions follow very closely their European model. See Asok Kumar Das, “Prince Salim and Christian Art”, in Nuno Vassallo e Silva, Jorge Flores (eds.), Goa and the Great Mughal (cat.), Lisbon - London, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum - Scala Publishers, 2004, pp. 166-168.

Print Copyright:

fig. 1 - Adriaen Collaert, after Jan van der Straet, Saint George Killing the Dragon, Flanders, Antwerp, c. 1580-1600; engraving on paper (25.2 x 18.8 cm). The British Museum, London, inv. 1901,0611.41. © The Trustees of the British Museum

@AMIRMOHTASHEMI

instagram

instagram