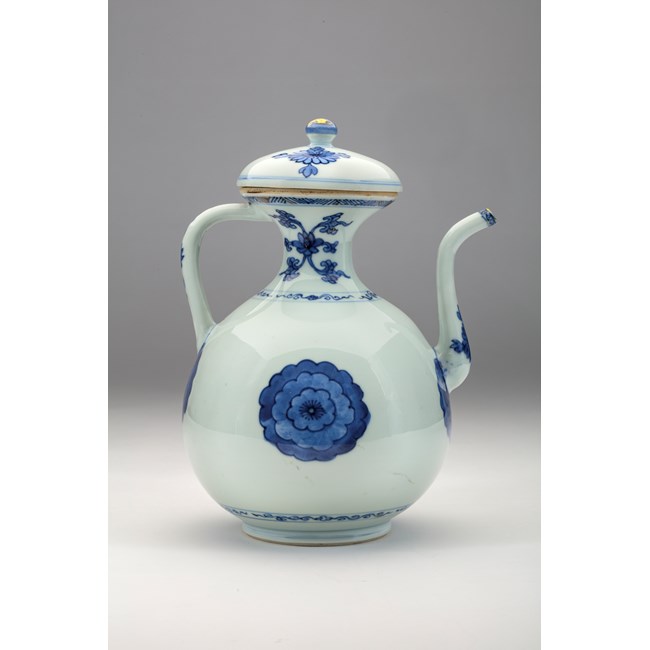

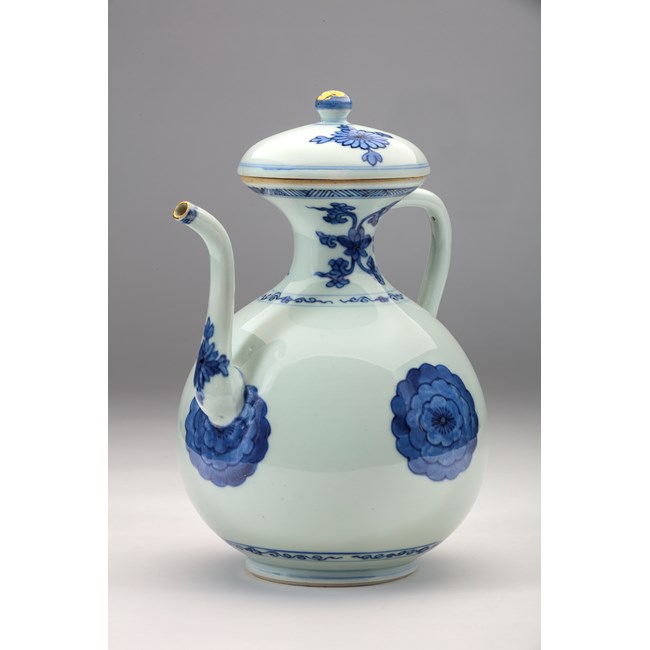

Porcelain Ewer 清康熙外销瓷青花执壶

Porcelain Ewer 清康熙外销瓷青花执壶

Made for the Indian market

China, Kangxi reign period (1662–1722)

Porcelain decorated in underglaze cobalt blue

26.5cm high, 16cm diameter

外销印度市场

中国,康熙年间(1662——1722年)

高26.5厘米,直径16厘米

Stock No.: A5314

Porcelain Ewer 清康熙外销瓷青花执壶

An Islamic ewer comprises a central chamber joined to a spout, foot, neck and handle. The vessel allows water to flow, for Quranic injunctions judged flowing water to be “pure”. Ewers of this type have their origins in Iran and the Middle East, and were introduced to India by Muslim invaders in the late 13th-early 14th century. In India, they were employed for handwashing and became a practical vessel for hospitality. Visitors were greeted by pouring water over their hands and feet into a basin; the liquid could be delicately scented rosewater.

The profile of the ewer, with its deeply indented neck, bulbous body, domed lid and upright spout and handle, conforms to Indian metal prototypes of the 17th century.1 Such ewers were commonly used and made in the subcontinent and in lands across the Middle East. A Chinese porcelain ewer of similar form, decorated in overglaze red enamel and gilding, and dated to the early 18th century, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, having been acquired in Iran in the 1870s.2 Similar ewers, one bearing Ottoman silver gilt mounts, are preserved in the Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul.3

The vessel is made of porcelain and decorated with a slightly greyish-blue cobalt with a simple pattern of four blossoms round the belly of the ewer. The undecorated white ground that surrounds the blossoms simulates the polished surface of metal and is not typical of Chinese porcelain painting that loved to fill entire surfaces. Flowering lotus scroll decorates the neck, and the patterns are bordered by scrolling and hatched bands. The simplicity of the design and its calm balance enhance the shape, and all point to production geared towards the Islamic market.

Footnotes:

Mark Zebrowski, Gold, Silver and Bronze from Mughal India, New Delhi, 1997, pp.139-140, 218-219.

Rose Kerr and Luisa E. Mengoni, Chinese Export Ceramics, V&A Publishing, London, 2011, p.108, pl.152.

John Ayers and Regina Krahl, in collaboration with Nurdan Erbahar, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul. A Complete Catalogue, vol.III, Qing Dynasty Porcelain, London, 1986, pp.935, 1192.

@AMIRMOHTASHEMI

instagram

instagram