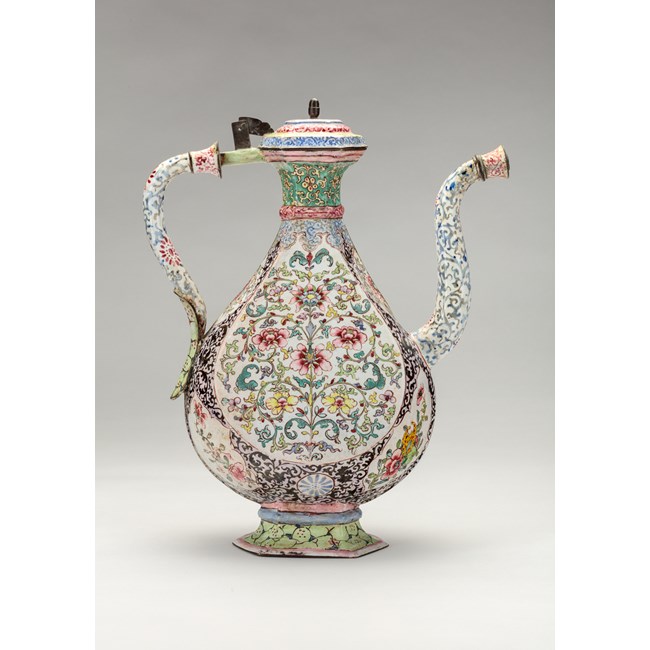

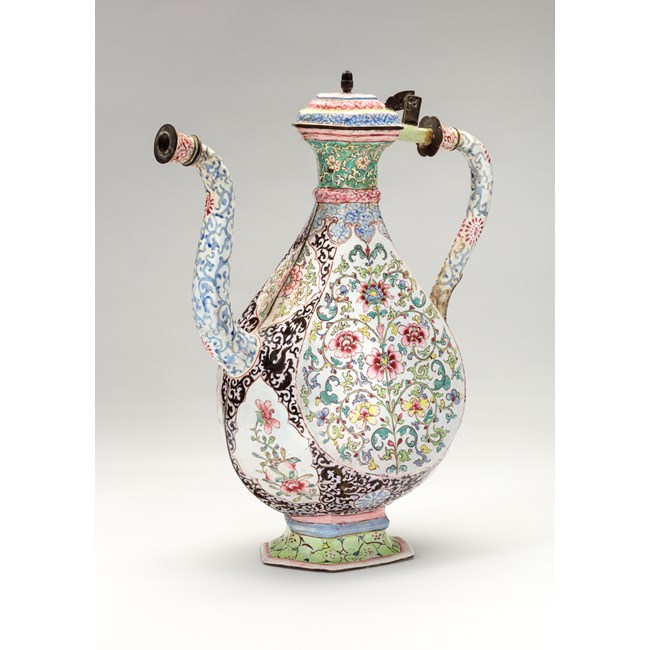

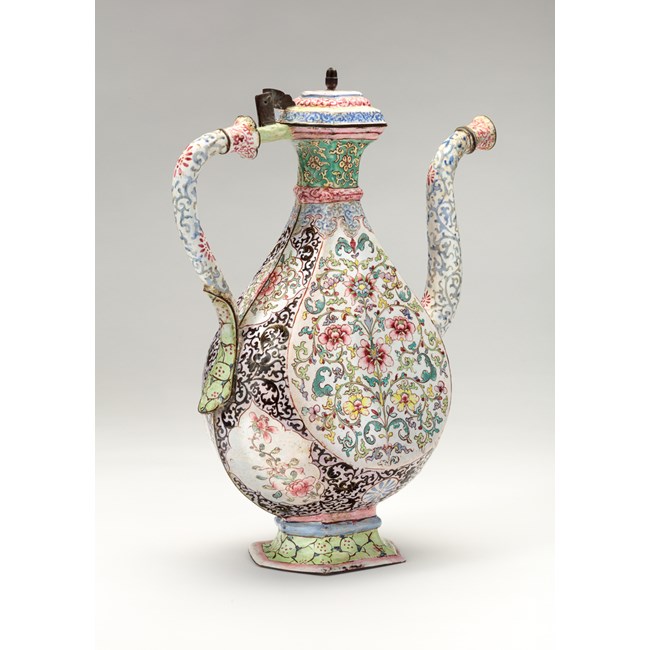

Ewer Made for the Indian Market

Ewer Made for the Indian Market

Guangzhou, China, 18th century

34 cm high, 28 cm wide

Copper enamel

Provenance: UK private collection since the 1970s

Stock no.: A5160

Ewer Made for the Indian Market

The vessel is formed from beaten copper to give a complex shape, namely an ewer destined for the Middle Eastern or Indian markets. To create such vessels, copper sheets were cut to an appropriate size and then pressed or hammered into the required shape. Moulds may have been used for the more common forms. The extremities – finials, handles, spouts, feet – were slotted into the body and the edges folded in on themselves. As far as possible soldering was avoided because soldered joints could become detached or loose during the enamelling process, thereby damaging the enamel surface. Once the vessel was assembled, it was smoothed and cleaned on every facet, in preparation for painting. A base layer of enamel was applied, usually white in colour, and this counter layer also helped bind jointed sections together, helping prevent cracks and the flaking off of subsequent coats of enamel. The piece was then fired for the first time in a muffle kiln. Muffle kilns were small ovens that generated a heat of around 700-800 degrees C.

The most important and complex stages in the production of painted copper were the refining, painting and firing of the enamels themselves. It is likely that craftsmen employed the same readily-available enamels that were used to decorate porcelain. In many cases, such as this ewer, the palette of enamel colours used was the same as that used on porcelain. That palette included ruby red and pink derived from colloidal gold, giving rise to the European term “famille rose”. Famille rose colours also encompassed opaque lead-stannate yellow, and lead-arsenic white. White enamel, when mixed with other colours, enabled a wider range of pastel shades than ever before.1 This extensive palette was fully used in the complex floral and geometric patterns on this colourful ewer. The patterns comprise scrolls of baoxiang or treasure flowers on the two sides of the body, arranged in upright, symmetrical strands that recall Islamic decoration. Geometric designs fill the rest of the body, the handle and the spout, while the foot and base of the spout are painted with a vivid green decoration of blossoms on a cracked ice ground. Cracked ice and prunus blossom symbolise the New Year, promise and hope. This is because prunus blossom appears on bare branches before the frozen ice has thawed, in late January or early February at the season of the lunar New Year.

Such dense floral and geometric designs in a rich array of colours were well suited for Muslim customers. Although the Quran, the Islamic holy book, does not explicitly prohibit the depiction of human figures, Chinese decorators would have been aware of possible problems with figural decoration. It was easier, and less risky, to incorporate the wide array of non-representational patterns available in their pattern books.

Footnotes:

1. Rose Kerr (ed.) and Nigel Wood. 2004. Ceramic Technology. Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5, part 12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp.638-645.

@AMIRMOHTASHEMI

instagram

instagram